In the world of conceptual art, where the idea takes precedence over the physical object, Instruction Art stands out as a form that invites collaboration, imagination, and interpretation. Rooted in minimalism and conceptualism, Instruction Art doesn’t just ask you to look at art—it asks you to create it, think it, or experience it through written or spoken commands.

What is Instruction Art?

Instruction Art is a genre of conceptual art where the artist provides instructions instead of—or alongside—a finished work. These instructions, often simple, poetic, or abstract, become the artwork themselves or guide someone else to create the piece.

In this form, the artist might never physically touch the final work. Instead, the idea becomes the medium, and the viewer or performer becomes the creator. This dynamic approach makes Instruction Art interactive, ephemeral, and deeply thought-provoking.

The essence of Instruction Art lies in its ability to transform a mundane action into a meaningful gesture. It blurs the boundary between artist and audience, object and process, language and experience.

Forms of Instructions

Instructions can vary widely in style and intent:

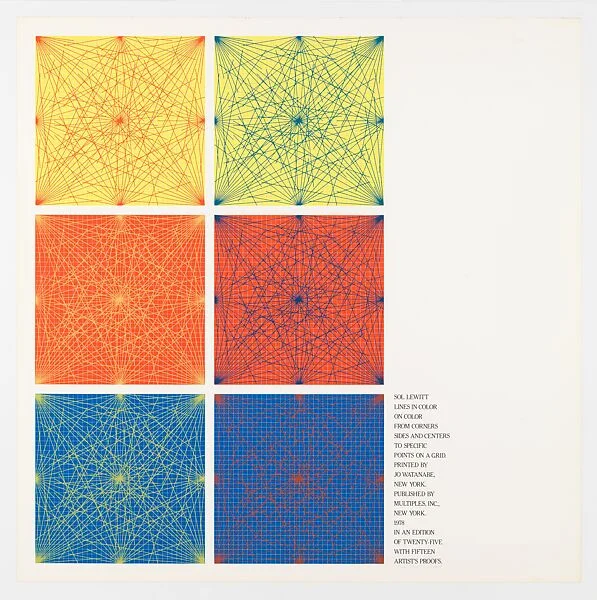

- Precise and structured (e.g., Sol LeWitt’s diagrams for wall drawings).

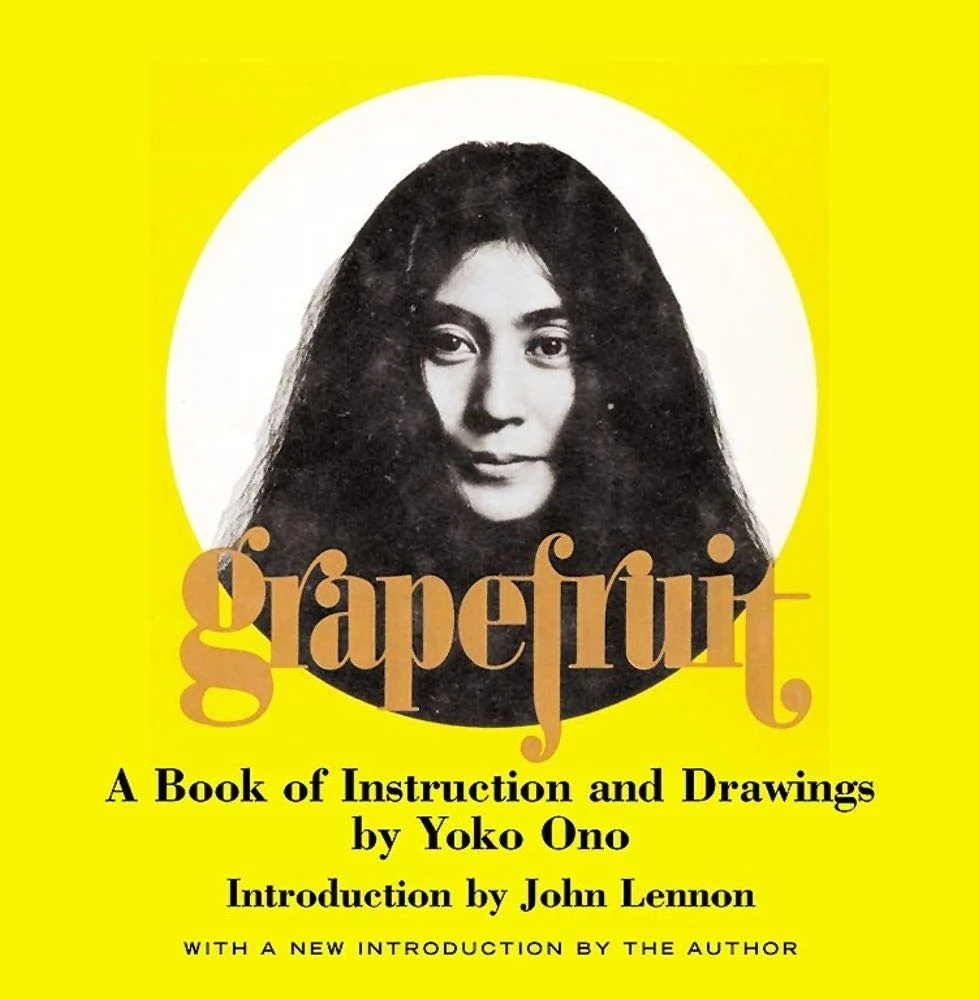

- Poetic or philosophical (e.g., Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit).

- Humorous or absurd (e.g., “Eat a color you’ve never seen before”).

- Silent or implied (e.g., artworks that require internal contemplation).

What Makes Instruction Art Unique?

- Non-material nature: Often, there’s no physical object at all. The artwork is the instruction.

- Open-ended participation: Anyone can follow, reinterpret, or ignore the instruction.

- Unpredictable outcomes: Execution depends on the reader’s perspective and creativity.

- Thought over form: It’s the mental process or the concept that matters most—not how it looks.

Origins and Key Artists

The roots of Instruction Art can be traced to the 1960s conceptual art movement, with major influences from:

- Sol LeWitt: Known for his wall drawings created by others following his written instructions. LeWitt believed that “the idea becomes a machine that makes the art.”

- Yoko Ono: Her book “Grapefruit” includes poetic instructions such as “Imagine the clouds dripping. Dig a hole in your garden to put them in.” Ono emphasized imagination and non-material creativity.

- Lawrence Weiner: Explored language as the medium, with works like “A 36″ x 36″ removal of lathing or support wall of plaster or wallboard from a wall.”

- John Cage: His music scores often contained instructions open to chance and interpretation, paralleling the ideas behind Instruction Art.

These pioneers emphasized that the concept alone could be art, and that execution was secondary—or even optional.

Examples of Instruction Art

Some works are performative, some meditative, others playful or profound. For example:

- Draw a line. Erase it. Repeat.

- Place one chair in each corner of a room. Sit in each for one minute. Think of a different person each time.

- Fill a glass with rainwater and leave it on a windowsill for one week.

- Walk backwards through a crowded space. Observe who turns to look at you.

- Write a letter you never send. Burn it and paint with the ashes.

These instructions function as open-ended invitations rather than strict directives. The final form may never be tangible but exists in the act, the idea, or the imagination.

Why Instruction Art Matters

Instruction Art challenges traditional assumptions about what art is and who can make it:

- Democratizes creation: Anyone can participate or interpret.

- Expands definitions: Art isn’t just a painting or sculpture.

- Focuses on thought: It values intention and mental engagement.

- Challenges authorship: Who is the artist—the writer or the doer?

- Breaks temporality: Some instructions may never be followed, or may be carried out years after being written.

It also encourages a conscious engagement with life itself. The art exists in behavior, in thought, and in transformation—often leaving no physical trace.

Modern Applications & Influence

In the digital age, Instruction Art has evolved and merged with new technologies and participatory culture:

- Social Media Art: Challenges like “Draw This In Your Style,” photo recreations, or collaborative prompts mirror the participatory essence of Instruction Art.

- Apps & Digital Prompts: Meditation and creativity apps often provide daily prompts rooted in conceptual and instructional thinking.

- Interactive Installations: Museums like the Tate and MoMA now offer exhibits where visitors follow steps to complete or transform a piece.

- Art Therapy & Education: Instructions help individuals explore creativity, memory, and healing through action.

- Gaming & Role-Playing Art: Games that blend real-world tasks with narrative reflect Instruction Art principles (e.g., Alternate Reality Games).

Instruction Art also intersects with activism, where instructions become tools of resistance or collective action.

Creating Your Own Instruction Art

Anyone can create Instruction Art. Here’s how:

- Choose a Concept: Think about emotions, daily rituals, or personal memories.

- Write Clearly or Poetically: Use short, evocative phrases. Be direct or cryptic.

- Focus on the Experience: What should the participant feel or discover?

- Let Go of the Outcome: It’s about the idea, not the result.

- Share It: In a zine, online post, art installation, or handwritten note.

Example:

Take a stone. Whisper into it your greatest fear. Leave it where someone else might find it.

Famous Examples & Artworks

- Sol LeWitt – Wall Drawings

LeWitt wrote instructions like “Draw 10,000 lines approximately one inch long” which assistants would carry out. He often never executed the pieces himself. - Yoko Ono – Grapefruit (1964)

A collection of poetic instructions like: “Tape the sound of the snow falling. This should be done in the evening. Do not listen to the tape.” - Lawrence Weiner – Statements (1968)

His art consisted of sentences like: “A square removal from a rug in use.”

This challenged the notion that the artwork had to be visible or tangible.

Final Thought

Instruction Art invites us to pause, reflect, and act. It’s a reminder that art can live in an idea, a whisper, or a command. Whether followed, interpreted, or left unrealized, the instructions themselves carry the essence of expression.

It encourages us to become artists in our own lives—to make meaning through motion, to sculpt our thoughts with intention, and to see beauty in the unseen.

So next time someone asks you to imagine, repeat, or rearrange—consider this: you might already be making art.

“If you were to write one instruction as art, what would it be? Share your version in the comments!”

Leave a Reply